Development aid

Table of Contents

In all African countries, it’s easy to find or recognize internationally funded aid projects. These projects all display large billboards indicating who built, planned, designed, and financed them. But even without these signs, one quickly learns to identify aid projects:

- Locally confined infrastructure that doesn’t match the overall level of infrastructure in the surrounding area.

- Infrastructure that appears one or two classes oversized.

- The projects adhere to EU or other industrialized nations’ building standards and requirements, which don’t seem to fit well in African countries.

- Upon closer inspection, the projects often evoke the feeling: “Who came up with this nonsense?”

Our impressions of these projects are extensive, but we’ll try to select and present one project from each category:

Road Construction in Sierra Leone

According to Wikipedia, Sierra Leone is one of the poorest countries in Africa. Strangely, this attribute appears in almost every Wikipedia article about an African country. The climate is tropical, and the interior is dominated by dense jungle. Many settlements are located along the country’s few roads. However, we get the impression that if you venture a little further away from the roads, you’re met with impenetrable jungle. For the people who live here, the roads are vital lifelines. The quality of the roads is typical for West Africa. Many roads are unpaved, but the main thoroughfares are mostly asphalted. However, the condition of the roads is often poor, and some consist more of potholes than asphalt.

That’s why we rubbed our eyes in disbelief when, on the last 30 km before the border to Liberia, we suddenly came across a road that looked like it was from another world. After a few hundred meters of marveling, a large project sign appeared next to the road:

This road was built and financed by the European Union to support and promote this economically disadvantaged border region.

A wide swath was cut through the rainforest for this road. Extensive earthworks were carried out to ensure a level and straight road surface. The road is significantly wider than is typical in Sierra Leone. There’s even a shoulder. The asphalt is new and as smooth as on high-speed roads in Europe. The lane markings are as clear as in Europe. Unfortunately, in West African traffic, nobody seems to care what a solid center line means. That’s not a problem, though, because there’s nobody to overtake. We didn’t encounter another car on the entire 30 km of this road. It is, after all, an economically disadvantaged region.

For this reason, there are proper and sturdy guardrails along the road, especially on curves and bridges. Traffic signs are placed at regular intervals. Before and after towns, there are lay-bys with marked parking spaces. In some sections, the road even has solar-powered streetlights. First-class bridges span the rivers, and near settlements, there’s something very rare for Africa: sidewalks on both sides of the road.

Unfortunately, we don’t know what the road looked like before this EU project. But this new road seems completely out of place in Sierra Leone, and this remote border region now probably has the best road in all of Sierra Leone. We would even go so far as to say that many communities and regions in Germany, whether economically disadvantaged or not, would be happy to have such a road.

Unfortunately, we don’t know why the EU built a road in Sierra Leone. But for the people who live here, this road is undoubtedly invaluable. As already mentioned, roads here are lifelines.

We do wonder, however, why this road was built to such a luxurious standard, clearly meeting and probably exceeding many European standards. These standards belong to a completely different world, and we’re sure everyone in this region would have been overjoyed with a paved road, even if it had no parking spaces or traffic signs. If the road didn’t have guardrails, which are nowhere to be found in Sierra Leone and only obstruct wildlife crossings. Without streetlights, when most houses here don’t even have their own electric lighting. Without all the other bells and whistles.

If the EU is building roads in Sierra Leone in the first place, then we wonder how many more roads could have been built in Sierra Leone with the money spent here, if the common standards of local roads had been followed.

The EEAS (European External Action Service) proudly reports on this project: EU roads and bridges programme in Sierra Leone

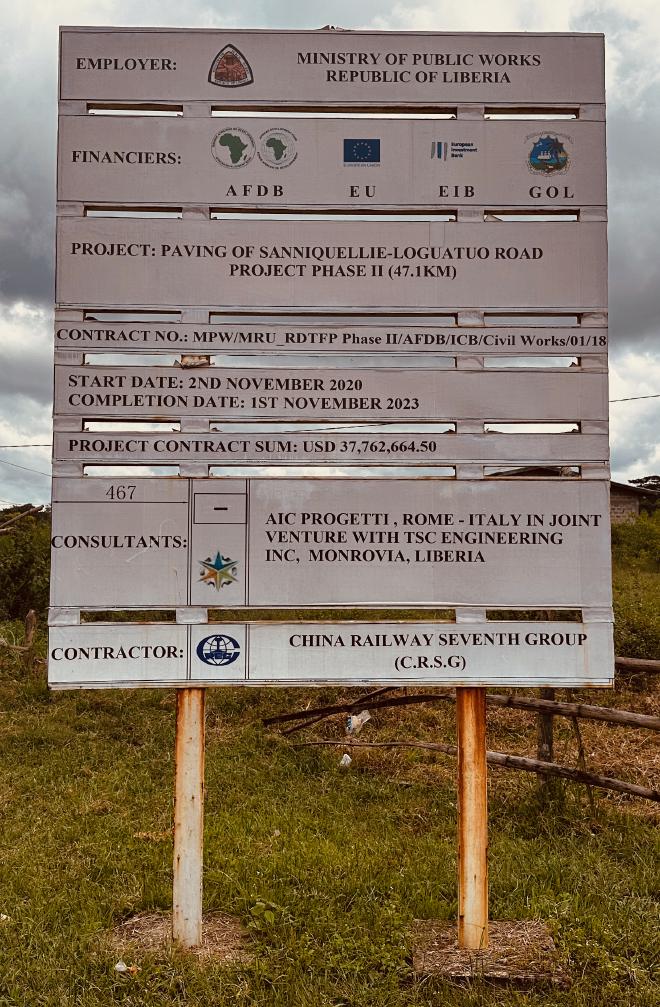

Road Construction in Liberia

The EU also finances road construction projects in Liberia. However, in Liberia, as in many other African countries, Chinese companies are very active and successful. China in Africa

In Liberia, we first encountered the situation that EU funding in Africa is being used for projects that are then carried out by Chinese companies. Unfortunately, we have no information as to why the EU allows or supports this. However, our own limited understanding of international economics and geopolitics leads us to wonder whether it wouldn’t have been more beneficial to European interests if such construction projects were carried out by domestic or European companies. The costs might be higher, but if the funds originate from the EU anyway, then in our view it should also be possible to link the disbursement of subsidies to the awarding of contracts to domestic or EU companies. If local companies undertake the construction, the money stays in the country, and both workers and entrepreneurs benefit. If an EU company were awarded the contract, a portion of the funds would flow back into the EU, strengthening the presence of European companies. As it stands, the money flows to China, further reinforcing China’s already very dominant influence in Africa.

The New Roads in Guinea-Conakry

In Guinea-Conakry, the presence of Chinese companies is very evident. Mining and road construction companies are everywhere, with large, inviting gates bearing Chinese characters, and the roads are dominated by trucks of Chinese brands.

We are traveling from Labé to Conakry. The journey is arduous. Due to the poor road conditions, we are making slow progress. But then, about 200 km before Conakry, we come across a newly built road. Constructed by one of the Chinese companies. Wide and smooth. You could easily mistake it for a major European highway. But we aren’t the only ones pleased with the new road. Many cars, motorcycles, and trucks overtake us at high speed. At times, we feel like we’re on a racetrack.

This comes at a cost. At regular intervals, we see wrecked cars on both sides of the road. Overturned trucks and cars that must have been launched off the road at high speed. Many wrecks, some of which appear to have been there for quite some time, are scattered alongside trucks, with pieces of their cargo still visible. It’s no exaggeration to say that there’s a wrecked car roughly every 2 kilometers.

We drive along this road at our usual 80 km/h and don’t actually find the road being difficult or dangerous. We interpret the situation as follows: many drivers in Guinea simply aren’t used to good roads. On “normal” roads, you can’t drive fast at all. Potholes, bumps, and tight curves force you to maintain a moderate speed. But on this road, you can really go fast. However, the high speed obviously exceeds the capabilities of many vehicles, their brakes, or simply the experience and caution of many drivers.

Border crossing from Guinea to Sierra Leone

At the border crossing from Guinea to Sierra Leone, we found this old sign.

Sugarcane Museum in Eswatini

Eswatini, formerly known as Swaziland, is one of the smallest countries in Africa and shares borders with South Africa and Mozambique. Politically, Eswatini has been independent since 1968 and is an absolute monarchy. Economically, Eswatini is doing very well compared to many other African countries. This is thanks to the intensive cultivation of sugarcane. In the plains, sugarcane fields stretch as far as the eye can see.

Before coming to Eswatini, we didn’t know much about this small country. But it quickly became clear to us that the country is almost entirely focused on the production of sugar.

Most of the cultivated land belongs to large estates owned by the Crown. However, many communities and private individuals also cultivate sugarcane.

Eswatini not only harvests the sugarcane but also has the factories to process it. The main products are:

- Molasses

- Brown cane sugar

- Refined white sugar

Eswatini thus profits not only from the cultivation of raw materials but also possesses the production capacity to manufacture the internationally sought-after end products. The largest share of Eswatini’s GDP is based on sugar exports. These exports go to other African countries as well as to the European Union. Eswatini has concluded trade agreements that allow it to supply unlimited quantities of sugar to the EU.

As good as all this sounds, it must be mentioned that the population is exploited for the sugar industry. Starvation wages, forced labor, 60+ hour workweeks, and child labor are common. But that’s another story.

Another major industry is the Coca-Cola plant. Due to South Africa’s apartheid policies, the company relocated from there to neighboring Eswatini in the 1980s. There, the syrup for the soft drinks is now produced for almost all of Africa. The proximity to Eswatini’s sugar industry is certainly an advantage.

In summary: Eswatini has a well-developed and lucrative industry built on sugarcane. On the other hand, the human rights situation in Eswatini is problematic.

In the heart of Eswatini, on a sugarcane plantation, there is a museum about the cultivation and processing of sugarcane. It was built with the support of the European Union.

We can only ask this one question: Why?

Great East Road in Zambia

The main connecting road between Zambia’s capital, Lusaka, and the border with Malawi in the northeast is called the “Great East Road.” This road serves both eastern Zambia and Malawi. The road, worn down by heavy traffic, is being gradually renovated and expanded.

Funded by the European Union.

As we travel along the Great East Road, we quickly notice two things:

- The sections that haven’t (yet) been renovated are in dire need of it.

- The renovated sections significantly improve road safety.

We can’t say whether the renovations have also led to an increase in traffic. Overall, the road renovation is a positive development for Zambia.

However, we have the feeling that this project was primarily a political one, intended to improve the EU’s standing in Zambia. We have no evidence to support this. Nevertheless, we have gained the impression that Zambia is quite capable of carrying out and financing important infrastructure projects on its own.

Funded by the EU, the renovated road was probably completed earlier and may even be of a higher quality than if Zambia had undertaken the renovation independently.

Bwanje Dam in Malawi

The East African country of Malawi is dominated by Lake Malawi, which stretches almost 600 km from north to south through the country.

Approximately 15 km west of Lake Malawi, the EU-funded Bwanje Dam was built. The project serves to irrigate agricultural land.

Malawi is a country that could certainly benefit from international aid projects. However, we don’t understand why a dam had to be built specifically for irrigating this region, considering all the environmental impacts associated with creating a new lake. The ninth largest lake in the world, with its very clear water, is only 15 km away. Surely the water could have been pumped from Lake Malawi for irrigation.

Hospital in Malawi

Another project in Malawi is the expansion of the hospital in Nkhotakota.

Many people in the region benefit from the improved medical care, and the construction contract was carried out by a Malawian construction company.

A helpful, manageable project, financed by Iceland. Unfortunately, we don’t know the reasons why Iceland funded this project.

However, we would like to use this project to highlight that simply building a hospital is not enough. The new hospital needs staff (doctors, nurses, and administrative personnel) who need to be trained and paid. Medical equipment not only needs to be purchased but also requires medical supplies, maintenance, and repairs. Even the building itself requires significantly more effort in the humid, warm climate to prevent deterioration.

Without this ongoing support, the new hospital quickly deteriorates into a moldy, dilapidated building with broken equipment and a lack of doctors.

Unfortunately, on our trip we saw far more failed medical facilities than trustworthy clinics.

Our Opinion

In summary, we observed that a tremendous amount of money and support flows into African countries. Unfortunately, we haven’t seen many projects that made us feel like, “It’s great that this project exists.”

Good intentions don’t necessarily translate into good results.

- Too many projects miss the mark when it comes to people’s needs.

- We don’t understand the prioritization of which projects are implemented where.

- The appropriateness of the projects often seems questionable to us.

- We have the impression that many projects are less about helping people and more about influencing the country’s politics or culture.

Every new project and every new impression we gained on our journey through Africa has repeatedly prompted us to discuss why things are the way they are in Africa and how we can truly help the people there.

In doing so, we have increasingly come to the conclusion that the people of Africa don’t need advice or directives from the outside. They can and must find their own solutions. For someone who has never been to Africa, it is probably extremely difficult to understand the vast cultural differences between African countries and Europe or the USA. Because of these differences, “obvious” solutions that may have worked well in other countries at some point are often unsuitable for solving the problems in Africa. Moreover, many circumstances, present from a Western perspective, a problem to be solved. But more often than not these cicumstances are not a problem at all from the perspective of the people in Africa, and no one feels that anything needs to be improved. As a result, external “solutions” are neither seen as improvements nor valued. Therefore, such projects are usually not very sustainable.

We believe that the greatest support that could be given to many countries in Africa would be to lift them out of their economic isolation and, at the same time, protect them from being exploited by large foreign corporations. It simply cannot work to deprive African countries of their resources and then try to promote them through development aid.